Rivest– Shamir–Adleman’s cryptosystem, which appeared in 1977, revolutionized cryptography by becoming the first public key encryption algorithm. In classical symmetric key encryption schemes, the same secret key is used for encryption and decryption. But the public key algorithm, also known as asymmetric encryption, uses 2 keys: public - with its help, anyone who wants to write you a message will encrypt it; and the private key. which is necessary to decrypt messages encrypted with a public key. RSA is a real breakthrough in the field of encryption and has been an example and workhorse of Internet security for 40 years. RSA is primarily an arithmetic trick. The work is based on a mathematical object called trapdoor permutation, which is a function that converts the number x to the number y in the same range, so it is easy to calculate y by x knowing the public key, but it is almost impossible to calculate x by y if you do not know the private secret key the entrance. (You can assume that x is plaintext and y is ciphertext.)

First, let's recall what is called a one-way function. Let ƒ : A → B be a function where the domain A and the range B can be arbitrary. Suppose the following conditions are met:

- Computing the value b = f(a) for any argument a belonging to A is relatively straightforward;

- Finding an element a belonging to A for a given element b in B such that b = f(a) is, in general, a relatively difficult problem.

Then we call f a one-way function.

For cryptographic purposes, the term "straightforward" in relation to computing b = f(a) from condition 1 means that there exists a computer program that performs this computation in real time. The notion of "real time," in turn, depends on the importance of the task, the power of the processor used, and so on. The opposite meaning is conveyed by the term "difficult problem" in condition 2.

For a public key e encryption system, a one-way bijective function fₑ : A → B is required. However, this is not enough. Another property needs to be feasible:

3. there is a secret for which finding the argument a from the equation f(a) = b becomes a fairly simple task.

Indeed, the owner of the secret (secret key d for decryption) is the recipient of the encryption, to whom it is intended. For him, the decryption process must be real.

At first, it seems that conditions 2 and 3 contradict each other. This is one of the main reasons for the appearance of public key encryption systems so late from a historical point of view. One-way functions that satisfy, in addition to conditions 1 and 2, also condition 3, are called one-way functions with a secret.

First, two sufficiently large prime numbers p and q are chosen, and the modulus n = p × q is computed. The numbers p and q are kept secret, while the modulus n is made public. Next, Euler's totient function φ(n) = (p - 1)(q - 1) is calculated, and a number e is selected such that gcd(e, φ(n)) = 1. The parameter e serves as the public encryption key. The value of φ(n) is kept secret. The coprimeness of e and φ(n) allows for the unique computation of a number d such that e × d = 1 (mod φ(n)).

When I talk about uniqueness, I mean satisfying the inequality 1 < d < φ(n). In other words, d is the multiplicative inverse of e in the group ℤₙ*. The value of d is the secret decryption key.

As a platform for the units of the original text, I will choose the ring of remainders ℤₙ. The units of the encrypted text will also be elements of the ring ℤₙ. The ciphertext unit c is obtained from the unit of the original text m by the following rule:

c = mᵉ (mod n).

I note that the resulting remainder c is written using the standard name, that is, 0 ≤ c < n - 1. To decrypt c, it is enough to know the value of the secret key d. Decryption is performed as follows:

m = cᵈ (mod n).

I explain how the equality just given turned out. First, let the unit m be mutually simple with n. Then, m ∈ ℤₙ, that is, it is an element of the multiplicative group ℤₙ*, the ring of remainders ℤₙ, the order of which is equal to φ(n). By Euler's theorem, mᵠ⁽ⁿ⁾ = 1 (mod n). The equality e × d = 1 (mod φ(n)) is equivalent to the existence of a number k ∈ ℤ, for which e × d = 1 + φ(n)k. Calculate:

cᵈ = mᵉᵈ = m × (mᵠ⁽ⁿ⁾)ᵏ = m × 1ᵏ = m (mod n).

First, it should be said about the complexity of factoring modulus n. Currently, no effective algorithm is known that allows you to find the multipliers of the decomposition of n = p × q. However, there is no proof of its non-existence. If such an algorithm had been found, the RSA system would have fallen out of use immediately. Indeed, the information about p, q allows us to obtain Euler's function φ(n) = (p - 1)(q - 1), and then use Euclid's algorithm to calculate the secret key d as the inverse element to the public key e in the group ℤₙ*.

However, to calculate the key d, it is enough to know only the Euler function φ(n) = (p - 1)(q - 1) = pq - (p + q) - 1 = n - (p + q) + 1. But in this case, it becomes known to us as the product of n = pq, so also is the sum of p + q = n - φ(n) + 1. This, of course, makes it possible to find p and q.

This implies that the ability to factorize the modulus n = pq is equivalent to the ability to somehow compute Euler's totient function φ(n). Both, again, lead to the complete declassification of the RSA system.

Let's see what else would make it possible to declassify the RSA system. Let's say, for example, that we know an efficient way to calculate all second-degree roots of 1 in a group ℤₙ*. First, note that finding two such roots is not difficult: y₁ = 1, y₂ = -1 = n - 1 (mod n). Let's try to prove that there are four such roots in total. List the residues modulus n that are congruent to 1 and -1 modulus p:

- 1, 1 + p, 1 + 2p, ..., 1 + (q - 1)p;

- -1, -1 + p, -1 + 2p, ..., -1 + (q - 1)p.

Similarly, I will write out all the residues mod n, comparable to 1 and -1 mod q:

- 1, 1 + q, 1 + 2q, ..., 1 + (p - 1)q;

- -1, -1 + q, -1 + 2q, ..., -1 + (p - 1)q.

If the residue mod n is comparable with 1 (mod p) and at the same time with 1 (mod q), then its square is comparable to 1 (mod n). The converse is also true. So, we have to find the same elements in the sets. The equalities 1 + pi = 1 + qj, -1 + pi = -1 + qj, with i = 0,1,2,..., (q - 1); j = 0,1,2,..., (p - 1), provide us with two already known solutions: y₁ = 1, y₂ = -1. The equalities like 1 + pi = -1 + qj, -1 + pi = 1 + qj with the same values of the parameters i, j give two more solutions: y₃, y₄.

Indeed, the first of them is equivalent to a system of comparisons:

pi = -2 (mod q)

qj = 2 (mod p),

for which i = -p⁻¹ × 2 (mod q), j = 2q⁻¹ (mod p). The whole system has a solution according to the Chinese Remainder Theorem. The solution y₃, as it is easy to see, is the only standard mod n, since all solutions differ by a term multiple of n = pq. From the last equality, we get another solution y₄ = -y₃.

So, I have established that there are exactly four roots of the second degree of 1 (mod n):

y₁ = 1, y₂ = -1, y₃, y₄ = -y₃.

Since y₃ ≠ 1 (mod n), the equation arising for some integer s is:

(y₃ - 1)(y₃ + 1) = sn.

This allows us to find: d₁ = gcd(y₃ - 1, n), d₂ = gcd(y₃ + 1, n) and obtain the factorization n = d₁d₂.

From all that has been said above, we can conclude that the ability to calculate all four roots of the second degree of 1 (mod n) is equivalent to the ability to decompose a module into multipliers: n = pq.

Let's note the most obvious recommendations here.

First, modules n₁, n₂ of different users should be mutually simple: gcd(n₁, n₂) = 1. Indeed, let's say, for example, n₁ = p × q₁, n₂ = p × q₂, in which q₁ ≠ q₂. Then gcd(n₁, n₂) = p, and this value, and hence the factorization n₁ = p × q₁, n₂ = p × q₂, can be calculated by anyone who knows the open data of n₁, n₂. The explanation is less obvious for the case of matching modules n₁ = n₂. If the keys match: e₁ = e₂ and d₁ = d₂, then such users are indistinguishable from the outside, and they are familiar with all the secrets of each other, which, of course, should be taken into account.

To prevent an attack using the same keys, it is important to choose large values for e₁, d₁, so that knowledge of the Euler’s function φ(n) does not allow the secrets to be calculated. It is also possible to carry out an attack if several users encrypt the same message with different modules n₁, n₂, ..., nₖ, but use the same public key e = k. In this case, using the Chinese Remainder Theorem, the message m can be recovered if the modulus n₁, n₂, ..., nₖ are pairwise coprime.

The pure RSA algorithm is vulnerable to a large number of hacking methods. Let's try to sort out some of them.

Each message in the RSA algorithm is represented by a number m, which does not exceed the number n. The number n must always be sufficiently large, which is determined by the choice of the numbers p and q. However, m is not subject to such a restriction; as a result, it can be of any size within the range 0 ≤ m < n, depending on the specific application.

If the practical application of RSA involves, for example, encrypting salaries x using the function c = Eₖ(x), then even if the salaries are very large, breaking the encryption becomes a relatively simple task. It is sufficient to iterate through the numbers from 0 to the maximum salary, encrypt them, and compare the results with the known encrypted value.

// pk = public key, c = ciphertext, ms = max salary, ci = ciphertext

def decrypt(pk, c, ms):

for i in range(ms):

ci = encrypt(pk, i)

if equal(c, ci):

return i

return NoneThe problem itself is based on the determinism of the encryption function E. When I talk about determinism, I mean that if we use the same numbers (or inputs) for encryption, then the result (or encrypted message) will always be the same. For example, if we have a number that we want to encrypt, and we encrypt it with the same key, then we will get the same result every time.

Therefore, under the same introductory conditions (e, n, m), the same ciphertext c will be obtained.

You can get rid of such an attack by encoding the plaintext before the encryption stage: c = E(Encode(m)). Encoding in this case should have a non-deterministic property, introducing random bytes into the text, so that (c₁ = E(Encode(m))) ≠ (c₂ = E(Encode(m))) when used repeatedly.

In the same turn, there should be such a decoding function that would return the primary plaintext without distortion: Decode(D(c₁)) = Decode(D(c₂)) = m. Modern systems use a special encryption scheme called OAEP (Optimal Asymmetric Encryption Padding) for this purpose. This scheme helps to create reliable and secure encodings that protect messages from hacking.

The RSA algorithm is able not only to encrypt information, but also to sign it. With all this, the function of signing information S is equivalent to the function of decrypting it D, and the function of verifying the signature V is equivalent to the encryption function E. In other words, if text x exists, then: S(x) = D(x) = xᵈ mod n, V(x) = E(x) = xᵉ mod n.

Due to this feature, there may be an incorrect use of the RSA algorithm with a single key, when both encryption and signing functions are used in application.

Let's assume there is a certain service that is able to sign the information sent to it with a private key k⁻¹. At the same time, secret communication with the same service is conducted thanks to its public key k. In this case, to find out the contents of the sent secret text c = Eₖ(m), an attacker can simply ask the service itself to sign the ciphertext: Sₖ⁻¹(c) = Sₖ⁻¹(Eₖ(m)) = Dₖ⁻¹(Eₖ(m)) = m.

But we can also assume that the service tracks previously accepted ciphertexts and does not process them twice. In this case, an attacker can act more cunningly by sending not c, but c' ≡ rᵏc (mod n), where r is a randomly generated number with the condition gcd(r, n) = 1. In this scenario, the following will happen: Sₖ⁻¹(c') = Sₖ⁻¹(rᵏc) = Sₖ⁻¹(Eₖ(r)Eₖ(m)) = Dₖ⁻¹(Eₖ(rm)) = rm. All that remains for the attacker is to multiply the result by the inverse of the random number: r⁻¹rm ≡ m (mod n).

To avoid such a problem, it is necessary to either use different encryption keys or different encoding schemes. For example, in practice, the OAEP scheme is used for encryption, and the PSS (Probabilistic Signature Scheme) is used for signing.

Developers often aim to use small open exponents to save on encryption and signature verification. Fermat primes are usually used in this context, in particular e = 3, 17, and 65537. Despite the fact that cryptographers recommend using 65537, developers often choose e = 3, which introduces many vulnerabilities in the RSA cryptosystem.

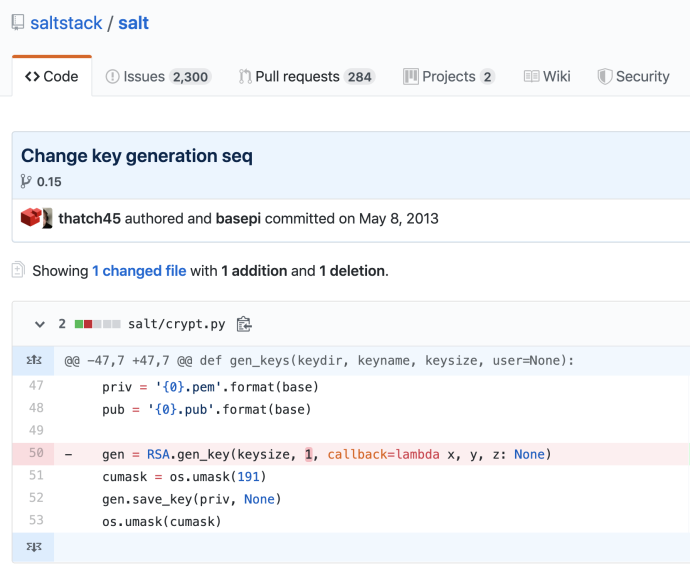

(Here the developers used e = 1, which actually does not encrypt plaintext at all.)

When e = 3 or a similar size, many issues can arise. Small open exponents are often combined with other common errors that allow an attacker to decrypt certain ciphertexts or factorize n. For example, the Franklin-Reuter attack allows an attacker to decrypt two messages connected by a known, fixed distance. In other words, suppose Alice sends Bob only "buy" or "sell." These messages will be associated with a known meaning, enabling an attacker to determine which message means "buy" and which means "sell" without needing to decrypt them. Some attacks with a small e can even lead to key recovery.

In 1643, mathematician Pierre de Fermat proposed the factorization method, which is used to decompose integers into prime factors.

If the prime numbers p and q used to generate the RSA key are "close" to each other, RSA can be compromised using Fermat's method.

Fermat's factorization method is based on the representation of the number N as a product (A - B)(A + B), where A is the arithmetic mean of the numbers p and q, and B is the difference between A and one of the primes. If p and q are close in value, then A will also be close to the square root of N.

This allows for efficient calculation of the values of A and B by incrementing A sequentially and checking whether the expression B² = A² - N is a square. If it is, then the prime factors can be calculated as:

p = A + B, q = A - B.

RSA is widely used in various aspects of life today, especially for data security and authentication. It forms the backbone of many protocols for secure information exchange over the Internet and beyond. Below are some areas of major RSA usage:

-

Secure Communication via HTTPS

RSA enables encrypted communication between the user's browser and the server, ensuring that transmitted information is not intercepted. RSA facilitates the key exchange once communication using HTTPS begins. When a website with an HTTPS address is accessed, the browser and server start RSA-based communication to create a secure channel. -

Document Signing

RSA allows users to digitally sign documents, ensuring authenticity and integrity. The sender attaches a digital signature with their private key, creating a unique signature for each document. This can be verified by the recipient using the public key, confirming the sender and ensuring no alterations. RSA is widely used in electronic signature services. -

Email Encryption via S/MIME

RSA is utilized in email encryption and digital signing via the S/MIME protocol, protecting emails from unauthorized access. It enables recipients to verify sender authenticity. -

VPN Services

Most VPNs use RSA to secure the communication channel between the client and server. RSA facilitates key exchange for encrypting traffic between the user and the VPN server, ensuring secure access—especially critical on public networks. -

Online Banking and Electronic Payments

RSA encryption secures online banking transactions and electronic payments. Banks use RSA for authentication and encryption, protecting sensitive data like credit card information and transaction authorization details. -

Government Systems and Electronic Voting

RSA secures data in government systems (e.g., e-ID cards) and enables secure citizen-government interactions. In electronic voting, RSA assures identity proof and protects the integrity of voting data.

This paper provided a detailed examination of the RSA algorithm, its mathematical foundations, application specifics, and significance in cryptography. The study highlighted the advantages of RSA as one of the most reliable asymmetric encryption algorithms, ensuring secure data transmission while preserving confidentiality and authenticity.

Through the implementation of RSA in Python for a simple messenger, the practical usability of RSA for message encryption was demonstrated, reinforcing its relevance and effectiveness in secure communications today.

Particular attention was given to the issues of cryptographic strength and potential attacks on RSA. It was established that the algorithm's reliability depends on the complexity of factoring large numbers, which is a computationally intensive task. Various attack methods on RSA were reviewed, along with strategies to mitigate them, allowing for an assessment of the algorithm’s vulnerabilities and limitations.

In conclusion, this paper confirmed the importance and resilience of RSA, emphasizing the critical role of correct implementation and application of the algorithm to ensure data security in modern information systems.